Wu Chen (Beijing Institute of Architectural Design and Beijing Urban Design and Renewal Engineering Technology Research Center)

Yang Lei (Beijing Institute of Architectural Design and Beijing Urban Design and Renewal Engineering Technology Research Center)

While the whole country is making concerted efforts to fight against COVID-19, we also need to take a scientific and reasonable look at every aspect of the epidemic. As the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated in its report released in 2007, at least 39 new pathogens had been discovered worldwide since 1967, and a new infectious disease broke out in less than every two years on average. This is in effect the result of increasingly grave urban problems. With global urbanization, diversification of urban functions, emergence of megacities and high-density cities, and greater inter-city connectivity and mobility, hub-type cities have gradually become major transmission routes of infectious diseases and major targets for epidemic prevention. Hence, it’s pressing to re-examine building healthy cities from the perspective of urban planning, develop innovative urban planning methodologies, and come up with strategies of epidemic prevention and control, which may present an important opportunity to transition from conventional planning.

Make cities healthy

As early as the mid-1980s, the WHO proposed the concept of healthy city and the vision of building healthy cities, and promoted building healthy cities as a global action strategy. In essence, cities provide space for people to live and work, and healthy city is an urban development pattern that takes into account society, economy, and every other aspect of a city with people’s mental and physical health put at the center of urban planning, building, and management, a health promotion process in different areas and at different levels that the government mobilizes every citizen and social organization to be collectively committed to, and a process of creating the best environment for human settlement. Making cities healthy hinges upon scientific urban planning methodology and advanced urban management pattern.

Health City Novena in Singapore Photo: Singapore’s Ministry of Health

Building healthy cities originated from Toronto, Canada, where progress was made in building healthy cities by developing healthy city plans and health management laws and regulations, taking public health safety measures, and encouraging the public to participate in urban health development, with health communities as the basic building blocks. It gained steam later in the US, Europe, Japan, Singapore, and Australia, where it gradually became an international action. International practices provide us with precious lessons in building healthy cities. For example, as a city keen on improving people’s health and happiness through urban building projects, London developed a series of instruments of rapid assessment on health impact to have an overall evaluation over development projects and planning policies, which played a significant role in promoting public and urban health; Vancouver came up with A Healthy City for All: Vancouver’s Healthy City Strategy 2014-2025, where it’s proposed to build Broadway Corridor for enhancements to public transit, improve the sidewalk design, and introduce a bike sharing programme as part of a package of measures it laid out for green travel, to ensure trips on foot, bike, and transit exceed 50%; and the Health City Novena under construction in Singapore, covering an area of 17 hectares and consisting of 13 buildings, will offer emergency treatment, medium and long-term nursing, and education & training, to evolve into the country’s medical and commercial hub with a specialized, people-first, and market-based approach.

China’s campaign for building hygienic cities in 1989 set the stage for developing healthy cities across, the country. In 2016, as the Healthy China 2030 strategy was implemented and the 9th Global Conference, on Health Promotion held, China entered a brand new, stage of healthy development of cities.

Challenges confronting healthy cities

As the history of global urbanization demonstrates, the 50% urbanization rate is the bottom line. Healthy development of urbanization will play a decisive role in China’s sustainable development in the next 20 years, otherwise serious urban problems are likely to occur. Reasonable flow and efficient concentration of all sorts of elements are inevitable in the process of urbanization, and the transmission of infectious diseases relies not only on the neighborhood effect of space, but increasingly on connection and mobility of urban networks. As the transmission of viruses is greatly affected by the pattern, structure and functional layout of urban areas, and development level and coverage of urban networks, building healthy cities still presents an enormous challenge for China.

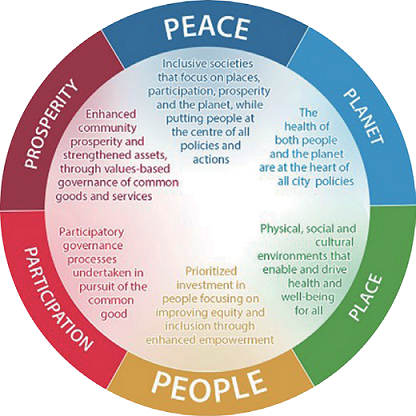

Vision of building healthy cities Photo: World Health Organization

Excessive functions of the downtown of a city, its over-high population density, and excessive concentration of urban elements, would undoubtedly heighten the risk of virus transmission during the outbreak of an epidemic, exposing such problems as ambiguous functional partitioning among groups within a city, undefined inter-city cooperation boundaries, and deficient inter-regional horizontal coordination mechanism. Hence, it’s imperative to re-examine the urban development pattern and explore more scientific development models and systems.

At a time when every minute counted in the battle against COVID-19 to save lives, Wuhan swiftly designed and built Huoshenshan and Leishenshan, wo makeshift control centers, allowing patients to get treatment more rapidly and channeling more medical resources. It came as a stark reminder that we have to reserve spatial and strategic space for any future emergencies in planning homeland space to provide optimized emergency space should any disasters occur.

The outbreak of COVID-19 coincided with China’s Spring Festival travel rush, a period when urban-rural migration usually reaches the peak. Many villages took drastic lockdown measures to curb the spread of the coronavirus induced by imported COVID-19 cases, which would result in disrupted supply chains linking urban with rural areas as village roads are an integral part of a well-functioning society and the channels for the flow of resources. The key is to have unimpeded supply chains between urban and rural areas and reasonable deployment of resources rather than impose village lockdowns.

Healthy cities in London, UK Photo: London Healthy Urban Develop- ment Unit

Cycle lane in Vancouver, Canada Photo: Vancouver City Planning Commission

Nature is like a mirror Photo: Pixabay

Toronto of Canada: origin of healthy cities Photo: Municipal Gov- ernment of Toronto

Lockdowns led to shortage of protective gear and of necessities of life, and traffic controls made it difficult for medical staff, patients, and workers at the grassroots level to get around, revealing a gap between current urban management and governance and what urbanization essentially requires. In other words, the relative static and fragmented management and governance pattern no longer satisfies the need of cities in modern times, necessitating the employment of intelligent technologies to improve urban management and governance.

COVID-19 has also exposed vulnerabilities of China’s public health emergency response system and mechanism, such as lack of prior assessment on the capacity of designated hospitals for COVID-19 patients, forethought of ensuring receipt and distribution of medical supplies during emergency response, and overall consideration of any logistics and services needed in transport hubs or hard-hit areas in the wake of lock down. There is a pressing need to enhance national and local emergency response systems to better cope with major public health emergencies of great complexity and strong impact.

Innovate to cope

Urban planning plays a vital role in prevention and control of infectious diseases. Specifically, at the macro level, we can shape urban form and development pattern with urbanization and large transport hubs, and at the meso and micro levels, we can reduce pollution exposure and guide evacuation with improved space design. As traditional planning has proved to underperform in quantitative analysis, we’re in dire need of innovative planning to contribute to building healthy cities. Mathematical modeling would help city planners and managers carry out quantitative analysis and simulation of complex urban phenomena and processes from an urban system perspective and have an overall assessment on social, economic, and environmental impact posed by epidemics. Such an approach can play a part on the following fronts.

First, build multi-center urban development structure. The advantage of a multi-center landscape lies in the fact that sub-centers can take on some of a city’s functions and be functionally complementary with one another or with central business districts (CBDs), which helps reduce the pressure on downtown areas and deliver an efficient and livable urban form. Hence, it’s advised to predict different development scenarios of urban multi-center groups and take into account all sorts of strategic planning combinations.

Second, set aside strategic space in planning. On one hand, it would optimize reserved strategic space for urban functions and provide some resilience for an intensive, efficient, and structurally-improved city to deal with any uncertainties of urban development; on the other, it would help meet any possible needs in the future with facilities for emergency response. Hence, it’s advised to have a reasonable planning of the area and distribution of strategic space on a quantitative level to improve the overall allocation of land resources of a city.

Third, predict and diagnose the mobility of urban systems. Mobility not only helps spread epidemics, but contributes to epidemic prevention and control. On one hand, stemming migration is key to combating epidemics; on the other, transport system plays a significant role in disaster prevention and mitigation, as the timely delivery of anti-epidemic and medical supplies, cross-regional deployment of medical staff, and supply of daily necessities wouldn’t be possible without mobility. Hence, it’s advised to conduct a systemic quantitative analysis of urban population evacuation routes, proposals for allocating resources, the basic logistic system, and urban-rural supply chains.

Livable life Photo: Leah Kelley

Fourth, have a scientific assessment on the impact of spatial elements. Reasonable planning of urban spatial elements not only helps maintain coordination and operation of urban space and its basic functions, but at the same time would help prevent crisis from occurring and spreading and reduce unnecessary losses should any public contingencies occur. Hence, it’s advised to have a scientific interpretation of the health of urban space, with which to have a comprehensive, real-time, and dynamic acquisition of data and information pertinent to urban spatial elements, carry out urban management and governance monitoring, analyze positive and negative effects of spatial elements on healthy cities, assess the coverage of public services and the equitable level of access to public services, conduct timely risk early warning of such issues as scarcity of resources, and make cities more capable of resisting threats.

Fifth, put in place an emergency response system. Prevention and control of infectious diseases has been rarely touched upon in existing urban disaster prevention and mitigation plans or medical and health care programmes. Hence, it’s advised to categorize cities based on population size and levels of epidemic prevention and control, appeal for the move to incorporate epidemic prevention and control into a holistic urban disaster prevention and mitigation plan, and establish an emergency response system for urban public health emergencies.

Epidemic is like a mirror. While testing the adaptability and resilience of China’s cities, it also signals the need for urban planning transition. We look forward to a significant role of planning in contributing to building a healthy China.

This article was funded by the Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Future Urban Design of Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture (for the research on key technologies for urban space development decision-making-based system: with six downtown districts of Beijing as examples UDC2018030611).