Introduction

On January 12th, 2021, the first issue of ‘Planning Eureka!’ held by UPSC was launched online with the topic of ‘City, Culture and Space’。 Professor Greg Clark, global advisor on cities, and academician of the British Academy of Social Sciences, gave a report entitled ‘DNA of the City’. The following is the full text of the presentation.

(This article has been reviewed by Professor Greg Clark)

Over the last 5 years, we’ve written and published three reports called ‘Culture’, ‘Value’ and ‘Place’, thinking about the role of culture in cities, and that has resulted in a new project that we are now writing now called ‘The DNA of Cities’.I’m going to talk this morning a little bit about this idea of decoding urban identity and the idea of cities being something like living organisms with their own genetic code that I think supports, in a sense, this idea of the critical role of culture in cities.

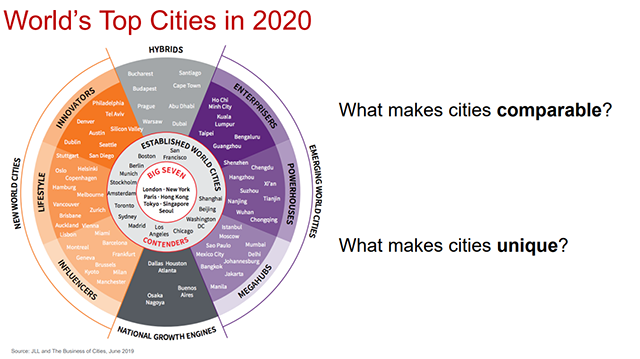

To put it at its most simple, what I’ve become very interested in is not so much how we can compare cities, what make cities comparable, but what makes each individual city unique, and what makes that city unique, we might call its culture. If we could understand and utilize the uniqueness of each city, I believe that this can be good for the design, the planning, the architecture of the city.

It may also be good for the participation of the urban populations in activities that make them active, increase social capital, and create health and well-being. I believe that understanding culture in this way can create strong individual identity for the city and can grow the city’s influence and its soft power. I believe that this way of understanding cities also allows us to think in much more detail about the resilience, the sustainability, and the agility of cities moving forwards, their ability to cope with change and to make change happen.

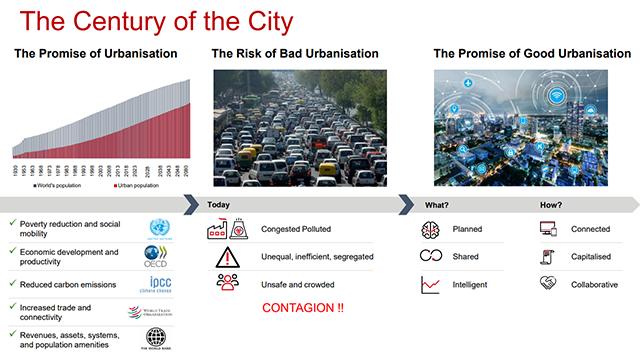

As we think about this idea of decoding urban identity, I’d like to put this in the context of, what I would like to call, ‘the Century of the City’。 The data is well-known that we are moving from a period in 1980, when about 40% of the 6.5 billion people living on our planet were in cities, to 2080, when about 80% of 9.5 billion people living on our planet will be in cities. A doubling of the percentage and a tripling of the number of people living in cities over a 100-year period. We are entering the fifth decade of this century now, and this century is a fascinating century for those of us who are interested in cities because it is the century where the city is becoming the dominant form of human settlement.

We know that, other things being equal, cities are good for us. We have many studies, that you see in the bottom left-hand corner of my slide, reminding us that cities are good to reduce poverty and to improve social mobility. Cities are good for productivity; they make workers and firms and capital more productive. Cities are environmentally efficient on average per capita. Cities can increase trade and connectivity, anchoring corridors of exchange. Cities produce assets, the revenues and systems that enable us to support population settlement to also provide services. So cities are good for us.

Figure 1

We know that we can have either good urbanisation or bad urbanisation. It’s quite possible that the carrying capacity of our cities can be easily over-reached if we don’t invest wisely and carefully in good urban planning, efficient land-uses, investment in the right kinds of infrastructure as well as investment in the systems and services the population needs. If population growth outstrips our investment in the carrying capacity, we get bad urbanisation very quickly. If we are able to continue to invest in the carrying capacity of a city, we can have good urbanisation with all of the promise realised.

Now, in the current period, as the world has been addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, part of the challenge of bad urbanisation has been the reminder that in certain cities, through the high levels of interaction that it causes, the face-to-face and face-to-place activities that cities facilitate has also increased the contagion in cities. Cities have been seen to be the places where the contagion has been worse. The world’s attitude towards cities has been changing a little bit in the past six months as in different countries, in different ways, people have begun to see cities once again not so much as the wonderful invention of humankind but cities, perhaps, are places of danger and problems.

Now, for these reasons, it’s very important, I think, for us to refresh our understanding of the DNA of cities, the purpose of cities, and to be clear about how we could make cities safe and make cities good. In my monthly column in the ‘Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors’ two months ago, I wrote an article observing that on the same day in one month, I had called all of my colleagues in New York to see how they are, and I had discovered that none of them were in New York. They were all staying in places outside of the city in a remote location. They had gone to the beach, gone to the lake or gone to the mountain. They had fled from New York because they felt that it was not safe. On the same day, I telephoned all of my colleagues and friends in Shanghai to discover that they were all in their offices, back in the city, working hard and making the city safe. It occurred to me on this day that there was a lesson to be learnt, that, if you like, there are different ways to treat the problems of the pandemic. In some cases, the idea that we should leave the city to be safe; in other cases, the idea that we should make the city safe to living. I think this divergence of approaches will now become very visible around the world over the next decade.

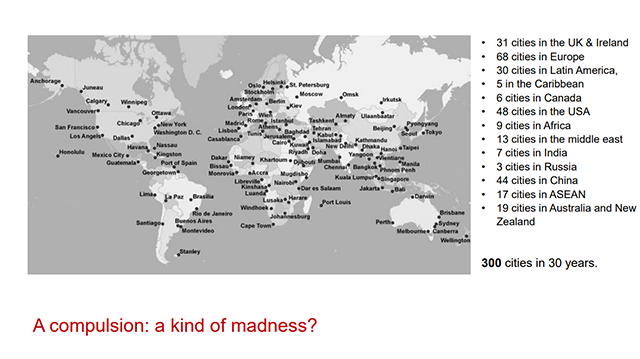

Now, over the last 30 years, I have visited 300 cities. This is perhaps a compulsion. Maybe you could describe it as a kind of madness to visit so many cities over such a period of time.

I had a Eureka moment of my own, when I was thinking about this the other day, asking the question ‘why is it that somebody has spent 30 years visiting 300 cities?’ Part of the answer, I think, of course, is that the century of the city that I have already described is a fascinating time to live. It’s a fascinating moment in the history of humanity, and I have a great yearning to understand what it means and how it works. Partly, it’s also because I’ve become very interested not so much in what makes all of these cities comparable but what are the metrics of connectivity or land use or competitiveness or liveability or quality of life, the more than 700 different benchmarks that we now have of how cities work and how we can compare them. Rather than that, I started to see these 300 cities each as a kind of individual friend, a personality, if you like, each one with its own particular characteristics, its own way of organizing itself. Because it has these different ways of being unique, it becomes fascinating simply to meet more cities in just the way we like to meet more people because they are individuals.

Figure 2

For these reasons, I’ve started a new project. For the last 20 years, I’ve spent a lot of time on this idea of what makes cities comparable. Our team in London, based at University College London, The Business of Cities Team, has done many, many large data studies on what makes city comparable. This has allowed us to review the hard power of cities, the advantages that one city has over another, the particular and distinctive ways in which cities are organized. We have been able to study, compare and seize all of those hard measures that I spoke about before, but increasingly, I realise this kind of study of the comparative aspects of cities is only rarely useful. If we also understand, through study, the unique dimensions of cities, the things that give each city its individual qualities, characteristics and personality, if you like, the DNA code of each city is essential to understand if we are going to really understand how we can help that city develop, how we can understand its possible future, how we can begin a new dialogue in that city about what needs to be planned, what should be designed, what should be built and, of course, the things that should not be planned, designed or built.

Figure 3

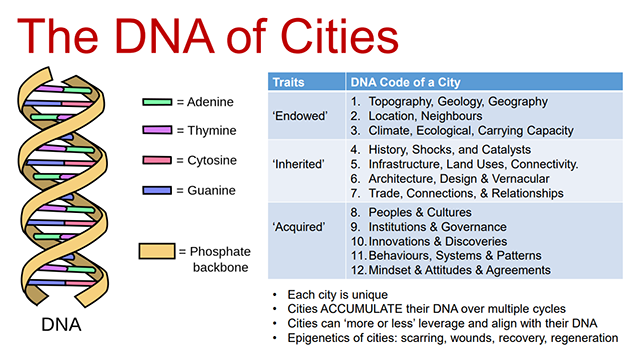

We began to think about this question of the DNA of cities. What really is it? If each city is a living organism, and each city has its own DNA, what are the strings of that DNA? We began to see that we could talk about 12 different things that we have developed into three groups. I’m going to talk about them very briefly now and then a little bit longer in a minute.

Figure 4

Firstly, we see a group of what we might call ‘endowed characteristics’, characteristics that are, in a certain sense, given by the planet to the city itself, things that the city does nothing about but the city emergence in a certain location, in a certain place, in a certain climate.

The second is the group of what we might called ‘inherited DNA strings’, things that the city receives from history, things that come from previous cycles of development and perhaps, even things that have been dormant for a period of time but then reclaimed, a kind of heritage. The heritage has many dimensions to it in terms of shapes and sizes and relationships and other things.

Thirdly, we talk about the set of traits that are ‘acquired’, things that are arriving in the cities as new ingredients, new assets or new drivers of change as a result of things that happen in the city or things that happen outside the city. We’ll talk much more about those things in a minute.

The idea of the DNA of cities is that if we understand the distinctive aspect of each of these 12 things, we can see how in combination each city becomes unique but also how a city can accumulate that DNA over multiple cycles. Cities can more or less leverage and align with their DNA. Cities can be more or less true to their DNA. They can use it in an optimum way, or they can ignore their DNA. It’s quite possible that cities can experience what we might call some epigenetics, some scarring, some wounds. Perhaps they can evolve themselves in processes of recovery or regeneration, if you want to put it this way, these two kinds of medicine that we could have in cities.

One kind of medicine is the medicine that deals with the things that make cities comparable. It’s the medicine of drugs, the medicine of diagnoses, the medicine that involves treating the symptoms of cities as being the same thing in every city. Another way of thinking about this is that because each city is unique, it’s possible to have a kind of customised medicine, a stem-cell therapy, a regenerative medicine, a medicine that is designed to tackle the unique DNA of each city rather than simply to see the challenges that happen in cities as being symptoms that are prevalent in many cities. Are we treating the disease, the symptoms, or are we treating the patient in their uniqueness? We can begin to think about urban planning, urban policy and urban regeneration as a kind of medical system. It has, on the one hand, the opportunity to be scientific and on the other hand, the opportunity to focus much more on the individual biochemistry of the city.

Now, if we take some of the examples of the cities that we have been studying for the book we are about to produce, you can see here that Shanghai and Singapore are two of the cities that we are working on. This way of thinking about the DNA of cities focuses not so much on the code data, for example, the size of Shanghai and its industrial structure, but much more on questions like the relationship between Shanghai and the Pacific Ocean. It focuses much more on the deep role of the Yangtze River and the Yangtze River Delta, eventually, in the development of Shanghai. It focuses more on this relationship between land and sea, and it makes us ask the question as to why 7000 years ago, a great population movement allowed people to emerge in Shanghai and why Shanghai has become, over many centuries, a place of change, a place of reform, a place of reinvention but also how Shanghai has, during its history, been a city that has been cosmopolitan, been highly globalised How it feels like Shanghai can develop an interesting understanding of its own historical DNA and to leverage that Shanghai fix to become one of the most important cities in the world.

Figure 5

When we look at a city like Sydney, we think not so much about the last 250 years during which European colonization, as a part of the British Empire, created a city that has become modern Sydney, but we think back over the last 50,000 years of the aboriginal city and settlement that existed in the area where Sydney is now, before. This area, abundant in nutritious produce, a place with great climate and a wonderful river supported a lifestyle of outdoors populations living and gathering together, creating important places of ritual and places of human celebration. If you like, there is an anthropological DNA in Sydney which still has a strong drawing power on the way that Sydney is shaped today. If we don’t understand that anthropological DNA of Sydney, we fail to see why the energy moves in certain locations and why specific places on the mapped Sydney have become very important.

When we think about a city like Singapore, sometimes called ‘the little red dot’, in the middle of this Asia region, it’s important, of course, to understand well before Singapore was a city of the British Empire, its location as a fantastic neighbour of trade in this strategic position enables Singapore to acquire a very diverse population at a very young period of time in its history. Singapore has a kind of 700-year experience as a city which has been important in term of fermenting exchange. A port city with wonderful focus on East and West collaboration. It’s no surprise, then, that in 1965, when Singapore became free of the British Empire and become free of its relationship with Kuala Lumpur and with Malaysia, that it started then to reinvent itself as a city that over five decades would, in a sense, establish a new nation, create a new multi-ethnic, multiracial cosmopolitan nation. It tried to combine a very high level of resourcefulness as an island city with very limited opportunity to secure resources by having no hinterland and using the absence of hinterland as a driver for innovative activity that enable it to trade once again with the world. In particular, of course, Singapore combined resource inventiveness, in particular, in relation to water, with innovation in public services to really improve the quality of housing and education and health care and other things together with a willingness to look out to the world for economical opportunity and to adopt very high standards, the ability to create visibility of the culture and business climate in order to create an attractive location.

We begin to understand the DNA of Shanghai, of Sydney and of Singapore are really important aspects of the narratives of the city that we need to understand if we are going to develop good long-term thinking about those cities. Now, we don’t have time in today’s conversation to talk in detail about Dubai, Tel Aviv, Istanbul, Vienna and other cities that you can see here. But it’s very clear, as we discover the history, the geography and indeed, the biochemistry of these cities, that each of them has, in a sense, embedded in its history and its culture the secrets of their own success which are not necessarily visible when one simply does these comparative studies. For example, although we may think about Dubai today as a city which is emphasising real estate, high levels of retail consumption and luxury tourism, in fact, Dubai is really a city of inventiveness, a city that began as a small fishing village that became one of the world’s epicentres of a pearling industry. Pearls have been captured in the water surrounding Dubai for many, many hundreds of years. It was in the 1920s, when cultured pearls are first created in Japan, that suddenly there was a shock or destruction to Dubai’s position as a global leading producer of pearls, that Dubai has to begin a new journey of reinvention in which through three or four cycles it shifts from being a fishing and pearling village to be a port city and from there to be an airport city with a key role in East-West relations, alternately becoming, in the last cycle, an important centre for business, for finance and for tourism. Dubai is on the road through its constituent’s reinvention to becoming a great city of reinvention into the future. Only by understanding the particular circumstances of each city can we begin to see how this role of understanding the DNA leads to a richer and a deeper understanding of what those cities can be again in the future.

Now, I stated at the beginning that there were 12 dimensions to this DNA. Let’s just talk very quickly about each of those. The first one we think of is the topography, the geology and the geography, the physical shape of the place where the city is. Usually, this has some very important dimensions to it with regard to land, with regard to water, with regard to wind. In particular, for cities that evolve during a period of maritime history, the winds have often shaped the way the city has evolved over time. We can think about London or about Glasgow in this respect where the winds that blew the ships from London to old Europe or blew the ships from Glasgow to old America created a particular kind of opportunity for these cities to trade its specific kind of goods and services and created, as they were, a set of relationships that have been very important.

We can also think of the second string of code of DNA as being about location and, in particular, about neighbours. What is the city close to, what is it near to and what does the relationship with those neighbours involve? If we think about New York and Philadelphia, actually, these two cities are very close to another. New York begins, of course, as a great trading centre, while Philadelphia begins, really, as a city providing settlement services for a population. New York became extremely inventive in the way in which trade has happened. Philadelphia became extremely inventive in the provision of human services: the first hospital, the first schools, the first social housing, the first fire brigade. Many things about serving population settlements are invented first in Philadelphia. While New York becomes the entrepreneur hub of the 20th century, Philadelphia becomes the city of conscience. These two cities are close to one another, but they develop different approaches which are, in a certain sense, complementary.

Now, the third string of the DNA of a city, we might call it climate: its ecological or carrying capacity, its ability to meet the needs of its own population using natural resources, or its requirements to innovate in how it does that in order to meet the need of the population. It’s very obvious in the case of Singapore where the need of decent water was absolutely critical. It’s also very obvious, as well, in relation to Vienna where the proximity to the Danube River creates an amazing ecological environment that can feed the large population including at the height of the Austro-Hungarian Empire when many, many people are living in the city.

The fourth elements of the DNA of the city we may call its history, its shocks and its catalysts. These helps us to see how the city has evolved through time, the things that have really shaped what has happened in this city and where it has responded to opportunities for change. We might, for example, think about Istanbul and be very clear that this city has had three names during its history. Byzantium, Constantinople and Istanbul have each had great empires that have created shocks and catalysts for how it has emerged. It has always been a city that drew opponent topography of being partially of Europe and partially of Asia, but this particular history has meant that imperial change has changed the character of the city and provided a new layer of activity each time.

Infrastructure land uses in connectivity emerge as the fifth example. Whether we are talking about the ancient Silk Roads and how they are being reused now in the 21st century to recreate system of trade or whether we think about the infrastructure that was created by the Roman Empire or by ancient Greece, we know that historic ruins and roads are very important in determining the orientation of cities and the ways in which they might evolve, creating a kind of permanent pattern of connectivity that determines land uses and other things.

We also know that - this is number six - the architecture, design and vernacular, the relationship between the built form and human life creates a character of how conversation occurs, what is possible to learn to develop a city. The relationship between shape and size and density of buildings and the way human life involves and how it performs are very critical. Trading relationships, connections and other kinds of relationships that evolve over time become very important. When we think about Barcelona, for example, its role as a Mediterranean port city and its trading relationships across the Mediterranean, as well as its relationships into the north and west of Europe because of its historic connections with the Frankish Empire and the Great King Charlemagne, produce a sense of ideas about Barcelona, that it is the most southerly city in the north of Europe and the most northerly city in the south of Europe as well as, of course, today being the capital of the Catalunya of the Mediterranean.

Now, if we look at the next set of DNA traits, we can think about people and culture and the role migration, in particular, has played in cities and how it creates a new society with its own values, dispositions, a set of connections. Ethnic and racial diversity can create a kind of competitive advantage for cities, that they’re cosmopolitan and global. Therefore, they provide opportunities not just to provide quality of life for diverse populations but also to be places where we can service global markets and produce products for global markets in one location.

Institutions that are flexible and are able to change the way they work over time and over geography will help to make cities that are continuously adaptable. Whereas, if the institutions become rigid, they will prevent the city from adapting.

We can think about what each city has discovered or invented. We have often asked each city that we speak to, what is the greatest invention of that city. So, in Glasgow, it is the television. Of course, in Philadelphia, we could argue that the greatest invention is America. The Declaration of Independence happened there. We could say in Vienna, many of the rules that established modern Europeans were created. Of course, in Shanghai, the Communist Party of China was invented. Very important discoveries and innovation in each of these cities.

We also know that there are key social behaviours, systems and patterns to the way people live that emerge in each of these cities. These are very closely related to the idea of mindset or attitude or agreement. For example, in London, there is a mindset that we could call ‘live and let live’, the idea that the city provides a certain kind of privacy for everyone. That privacy has the idea of ‘tolerate’ within it; people should be who they want to be and what they want to be.

These 12 DNA traits begin to give us another way of understanding our cities, and it has proved to be very rich to use these. We began to understand that there are five ways that the DNA of cities can be helpful. Firstly, it can help us to build a strong identity and affinity and pride; it can help us to create a sense of belonging. That is a very important way to use the DNA of the city. Secondly, it really enables us to see what the latent capacity and carrying capacity of the city is, to understand its limitations in a way that can be creative and purposeful. Thirdly, if we think about the DNA of cities, it enables us to anticipate the way the city might deal with the shock or the surprise of unexpected change. In other words, how resilient and agile the city might be when something unexpected occurs. It also enables us to think about how we can have a different conversation about the future of the city based on a more detailed understanding of its origins or its history. It also allows us to rethink, to continuously make and remake the socio-contract of the city and enables us to create a new consensus, a new understanding of what the next cycle of the next chapter in the history of the city is. Through our investigation into the DNA of the city, we have discovered that much more attention is paid to number one than to number two, three, four or five. We tried very hard in the work we are doing to really encourage people to use this more widely.

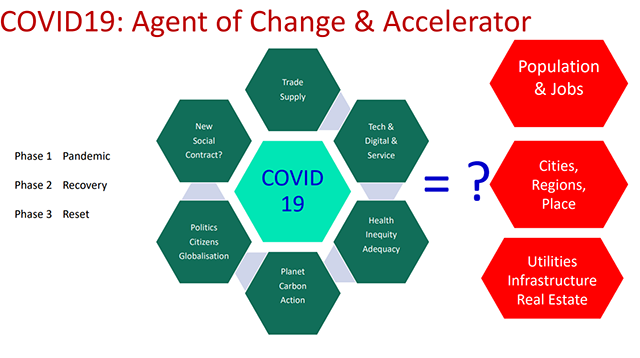

Now, COVID-19 has been a big shock for our cities, changing in the long-term how we think about issues to do with trade and supply, massively increasing the use of technology, revealing health inequalities and inadequacies, prioritising, again, the importance of the planet in human health as well as a long-term sustainability, changing the politics of how citizens interact with nations, states and how they interact with each other but also focusing much more on social cohesion, social capital, social solidarity. We think this is going to have big impacts on population and jobs, of what happens in the shapes of cities and regions and in the utility and infrastructure and real estate. This will play out over time, we think, in three different phases.

Figure 6

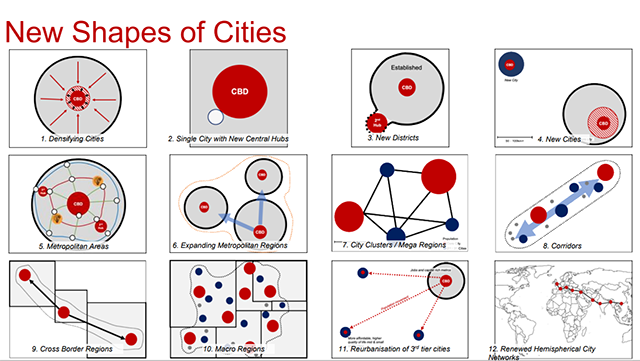

Understanding this enables us to see how our cities might change and evolve as a result of COVID-19 with some activities being downgraded and other activities being upgraded. We are right to recognize that cities are not recovering from the crisis as fast as national economies are. Therefore, there are some key challenges in helping our cities to respond to COVID-19, particularly in relation to the building environment and land uses where there are clearly some activities that are going to be accelerated, others that might be downgraded and some where there is a certain kind of uncertainty about how they will perform in the future. Now, one of the things we think COVID-19 will do is accelerate the evolution of our land uses into some new patterns of shapes. These are things, of course, that have already been happening in China where we see the movement much more towards poly-centric cities, regions, clusters and networks as you can see in slides six and seven and eight and nine and ten and eleven here. We think that COVID-19 doesn’t reverse the century of the city but really accelerate the new shapes that cities will have in these multiple forms over time.

Figure 7

Perhaps it gives rise to a new idea about how cities will work: not so much that people will live in physical cities and embrace the virtual cities, but that we will have a new kind of blended city where the relationship between citizens and cities may start to make some new choices about where they live, how they work and consume, and when and how they travel. This creates a city that has more porous borders with a larger geography in the city than it has before but with a greater use of choice in how land uses, infrastructure and others evolve. If you like, the impact of COVID-19 is not to reverse urbanisation but to distribute differently the ways that requires our cities to be more agile.

I want to come to my conclusions and say that through COVID-19, I think that cities are, in a certain sense, under attack. There is attention, and some parts of global media blame the cities for contagion. It’s very important, in this context, that we reassert the importance of cities and the role that they have played in civilisation and in creating the conditions for healthy and happy lives for human beings. At the same time, it’s also essential that we use our cities to drive the fixing of the planet, to tackle climate change and to create global prosperity. We need 6,000 cities to succeed, and we need the world to fall in love with its cities again. I think it requires skilful communication about what cities are, and I think the idea of the DNA of the cities helps us to communicate why is it we need cities and how cities work for all of us.

To my mind, this comes back to what I would say right at the beginning. It’s not just that cities are structures and systems and that cities operate as they were, as a hard kind of power in a built environment. It’s also that cities provide us with opportunities to think, to feel, to touch, to smell, to experience them differently. Cities have an experiential quality to them that allows us to dream differently. Cities allows us to think about how we can free ourselves from constraints and orders and rules and systems. They do, if you like, allow us, through that DNA, to find our own DNA and to become the people we are capable of being. Cities have a liberating aspect to them that allows people to find, in a very large group, the ironic possibility of being more of an individual, to find our sense of self, our sense of being and our sense of meaning.

We could summarise this by saying something that Winston Churchill once said: “we shape our cities and then our cities shape us.”